Boyle Heights Activists Take Aim At Art Galleries In Fight Against Gentrification

IN NEWS ON JUL 14, 2016 4:50 PM

The average household income at Pico Gardens is $23,000, or roughly one-fifth of the cost of one of the Alex Hubbard paintings that were on view when Maccarone gallery opened their doors in Boyle Heights last September, a few blocks away from the housing project.

As Carolina A. Miranda, the Los Angeles Times’ art critic, wrote in April, “the Los Angeles art world’s center of gravity has continued to migrate eastward,” and galleries are now opening not just in the Arts District, but also east of downtown, in Boyle Heights. The new galleries’ presence has been heralded by many civic boosters (at long last, a West Coast art scene to rival New York’s!) but here at Pico Gardens, in the lowland between the eponymous heights of Boyle and the L.A. River, the fear is hot and palpable.

“The galleries are playing a huge role in our neighborhood, we see them jumping the river, moving right next to public housing, threatening our rents,” Leonardo Vilchis, a longtime organizer and founder of Boyle Heights community group Union de Vecinos, told LAist.

Union de Vecinos cofounder Leonardo Vilchis speaks during the July 13 community meeting at Pico Gardens (Photo by Julia Wick/LAist)

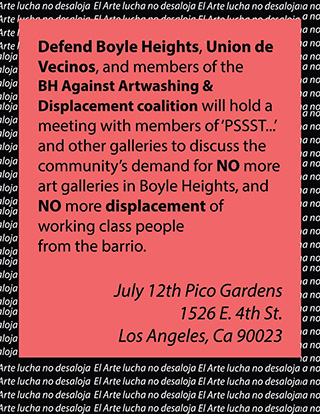

On Tuesday night, community members asked gallery owners to come and hear them speak at Pico Gardens, holding a heated public forum attended by crowds of activists and residents of both the public housing complex and the surrounding neighborhoods, along with a handful of gallery owners and employees. The message from the Boyle Heights community was clear: Leave, you are not welcome here.

The two-hour long meeting was organized by Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and

Displacement (BHAAAD), a new umbrella coalition of groups fighting against arts-based gentrification in Boyle Heights. A new generation of radical activist groups have sprung up in here in the ’60s-era birthplace of the Chicano civil rights movement, including groups like Serve the People and Defend Boyle Heights, both of which fall under the BHAAAD umbrella.Serve the People, a Mao-influenced collective known for both their anti-gentrification efforts and the weekly food and clothing distribution programs that they run in Echo and Hollenbeck parks, have made headlines in the past for their hard-line efforts to keep outsiders at bay. Both groups have also been involved withactions targeting PSSST, another upstart gallery in the area near the river.

“Defend Boyle Heights’ message has been kind of twisted into a we’re-against-artists mentality, but one thing that’s very important to recognize is that, as many of us already know, there’s a long history of artists in Boyle Heights, and this isn’t just something that happened in the past,” Giovannie Nuñez, an activist affiliated with a number of groups including Defend Boyle Heights and the Backyard Brigade, said. “We’re not against artists, we’re against gentrification.”

Los Angeles, as you surely know, is deep in the grips of an affordable housing crisis, and residents in a place like Boyle Heights are especially vulnerable to displacement. The neighborhood is overwhelmingly composed of renters (only about a quarter of residents own their homes) and the area has a median income of $33,235. For context, the median income for Los Angeles County is $62,400, and under housing guidelines, a family of four with a household income of $43,400 would qualify for services in the “very low income” category.

Meanwhile, the residential real estate market in Boyle Heights is “soaring,” according to Ivan Estrada, a real estate broker at Douglas Elliman. Estrada told LAist that the burgeoning art world presence will only make the market more desirable, especially as home prices become more unaffordable.

“It’ll be a gentrification type of situation, like what happened in Venice or downtown L.A. or Eagle Rock,” Estrada said, going on to outline the exact scenario that haunts many residents.

“I’ve had clients who were West L.A. clients who are now saying I can’t afford a house here, I can only afford an apartment, and I want to buy a house so I’m willing to move east,” positing that Boyle Heights will soon be “attracting a wider range of people who might not have seen it as a place to live in the past.” “For young couples, or single professionals, it’s definitely a great time to buy [in Boyle Heights], or even as an investment, to buy a duplex or a triplex and rent it out because we’re running out of areas where it’s affordable to rent anymore,” he continued, adding that Eastside rents will likely catch up to the ridiculous rates on the Westside “sooner rather than later.”

Elizabeth Blaney, who cofounded Union de Vecinos with Vilchis twenty years ago, said that even renters who live in rent-stabilized units can be forced out through harassment and other tactics, leading not just to their displacement, but also the loss of another affordable unit as it returns to market-rate prices following their departure.

“This is just happening really, really fast,” Vilchis said. “We need to slow it down so people can have time to understand what’s going on.”

It’s an imperfect situation,” a real estate professional who asked not to be named because of business concerns, told LAist. “You’ve got this gradient of money coming in, and there’s no way to stop that from happening,” he said, describing Boyle Heights’ geographic appeal as a place that’s “within the orbit of downtown, so it’s not unreasonable to go there from where some other activity is.” The character of the area, particularly in the industrial section on Mission Road, is also what makes the area attractive to him. “The smaller pockets of density mean you have the potential to control what’s happening enough to do really special things and not have some shithead open up next to you and feed off your heat.”

“Our attitude is that the right users will create a really radical appreciation and before you know it in ten years you’ll have this magical collection of businesses and users and operators and artists and it becomes the place to be among places to be,” he said. “And then you just go ahead and dump everything, but you’re selling it to people who’ve done well enough and been part of this special ecosystem so that most of them can afford to buy their buildings after years of a healthy run, and it’s the exact opposite of the Arts District.”

Looking east from the intersection of Boyle Avenue and 1st Street with downtown in the distance, circa 1998. (Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection)

Residents bristle at newcomers who they see as “Columbus-ing” over on the Gold Line and “discovering” the neighborhood, exoticizing the mariachis and vibrant murals into a romanticized commodity for their Anglo consumption, a la the tourist-friendly Olvera Street.

“How nice it must be to just get here when everything is so beautiful,” Edita Lopez, a longtime Pico Gardens resident, said through tears at the Pico Gardens meeting, speaking of the decades that she and other residents had spent fighting for the community, amidst periods of great violence. “Everything you see has cost us.”

Equally troublesome is the collective amnesia that seems to fall over certain Johnny-come-latelys as soon as they cross the river, and somehow see Boyle Heights not as one of the city’s“most historically and culturally rich neighborhoods,” but instead as a frontier for their taking. “It’s like a dream here with all the artists around,” Maggie Lee, a 27-year-old filmmaker whose work was being shown at 356 Mission told the The New York Times in February. “But it’s also desolate, and the only sound I hear all night are big trucks.”

The upper middle class trend blog formerly known as the New York Times has done a good job of stoking the fires in what they describe as “Los Angeles’s ever-expanding Arts District.” Never mind that the “Arts District” is across the Los Angeles River in downtown.

“There’s a sense of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys around here,” the Times quotes a 31-year-old painter to moved to a light-filled Boyle Heights loft eight months ago as saying.

“You still have to worry about making money, but it feels like you can make it work on little,” the artist told the Times. “There isn’t that daily grind. It’s mainly tacos and stray dogs and really nice people.”

But to the families who have raised their children here amidst great struggle, and to the generation of young Mexican Americans who grew up here and now grapple with how to have the community be a place that can grow with them without furthering displacement (see also:gentefication), Boyle Heights is no Neverland.

During Tuesday’s meeting at Pico Gardens, Delmira Gonzalez, another longstanding resident of the complex, talked about the long years of gun violence, when the streets were unsafe and there were no jobs for the community’s youth, and pleaded with gallery owners to listen to the voices of the residents. “We want you to hear about everything we’ve worked for, and everything we’ve suffered in order to be able to live here. These are homes for very low income people and we’ve fought for them.”

“Please, we don’t want you here, near our homes,” she continued. “Because we know that if those galleries are here, our rents are going to go up. And the price of land is going to go up, and we don’t want that. Please, think it through,” she said.

As Michael Lens, a professor of urban planning at UCLA who specializes in housing policy and equity told LAist, “It’s easy to look at Boyle Heights and say, ‘Oh well, things are getting better there, why are you complaining.’ But that would be completely ignorant of history. The people who live there have a lot of reasons to be distrustful of outside intervention, distrustful of new people moving in there, or of governments saying everything is going to be fine. Government and private developers haven’t earned the trust of those residents.”

“It’s important to know the history, and not just how the area culturally became a Latino enclave,” Lens said. Various forms of injustice have been visited upon this six-mile neighborhood over the years, like the construction of freeways that carved up the neighborhood fabric, environmental injustices, and poverty.

But the tensions haven’t just pitted community members against the arriviste gallery owners; they’ve also led to conflict between a subset of newer, more radical groups, and institutions like Self Help Graphics, a decades-old arts organization and pillar of the Boyle Heights community.

A group has taken over the main stage asking for outside art galleries to leave pic.twitter.com/gWVKRD75zB

— Steve Saldivar (@stevesaldivar) July 2, 2016

A little over a week ago, BHAAAD activists disrupted a Saturday afternoon program at Self Help Graphics’ space on 1st Street. The four-decade-old Chicano art space was hosting an “Artist Dialogue about Arts & Gentrification” when it was disrupted, and briefly taken over, by protesters from Defend Boyle Heights, Union de Vecinos, Ovarian Psycos, Serve the People, East Los Angeles Brown Berets and Backyard Brigade. Holding signs and carrying bullhorns, activists took over the main stage, demanding that all galleries leave Boyle Heights. The thirty to forty activists chanted “El barrio no se vende! Boyle Heights se defiende!” the groups alleged that Self Help Graphics had tacitly supported the galleries, were therefore complicit in the gentrification of the neighborhood.

“Boyle Heights is a low-income renter community. Get the fuck outta here with that argument that we need more art galleries. Boyle Heights has always been a cultural and artistic icon, with or without galleries. That is not a genuine and immediate need of the vast majority of community members,” members of Defend Boyle Heights wrote in a statement that they posted online, pledging that they will “continue to hold problematic forces in our community accountable.”

“We’re here on a daily basis dealing with these issues,” Joel Garcia, Director of Programs at Self Help Graphics told LAist. “It was disruptive, but we knew they were coming, so we gave them the space to share their concerns. We hoped that they would have stuck around to have an actual dialogue and look at things in a deeper sense.”

Raul Diaz, another longtime Pico Gardens resident, expressed doubt and frustration with the tactics. “I’m not an artist, I’ve probably been in Self Help Graphics three, four times in my life, but I know Joel [Garcia] from the streets because he walks the streets, he knows what’s important for our communities. Why are we going to go after someone like that who is trying?”

“If we’re going to do a movement, we do it right, we do it smart, we do it the old school way, or we do it no way,” Diaz said.

“Everyone wants to be heard, but this is a serious movement that is going to happen,” he continued, stressing the need to find ways to meet financial needs and tap into political support.

“Because or else, what is this? This is poetry night, people expressing themselves. That’s all this is right now. And I’m a supporter of poetry. Trust me, I am. But I don’t see no brainstorming coming up here.”

Can any of that radical noise have an effect, or is it all just that—poetry and noise?

For one young artist with a studio in Boyle Heights, the meeting at Pico Gardens was a turning point.

“No matter what angle I try to look at it from, my presence there is not welcome and has a violent impact in a low income neighborhood with a history of violence,” Cody Lee Edison told LAist. He’d already been struggling with whether to stay or not for a few months, but “after that meeting I decided I wanted to stand in solidarity with the community of Boyle Heights.”

“For me, this is a no-brainer and the easy right decision,” Edison said. “As for the art galleries around my studio they could send a clear and powerful message to the art world and to Los Angeles if they leave too. It is difficult to be an artist and navigate living in an expensive city like Los Angeles, however my dreams of success as an artist do not usurp the needs the Boyle Heights community. I wish I came to this conclusion earlier.”

As powerful as Lee Edison’s words may be, they are unlikely to sway like someone like Maccarone gallery proprietor Michele Maccarone, who Bloomberg describes as the “art dealer to billionaires who’s making collecting art cool again.” Galleries or no galleries (though there will likely always be galleries), the city remains radically short on affordable housing, especially units for very low income residents like those most needed in Boyle Heights.