COURTESY DEFEND BOYLE HEIGHTS AND BOYLE HEIGHTS ALLIANCE AGAINST ART WASHING AND DISPLACEMENT

On the afternoon of Saturday, April 28, sunny T-shirt weather in Los Angeles, a couple dozen people assembled outside the industrial building that housed the art exhibition and performance space 356 Mission to celebrate the space’s closure. Balloons hung from a stop sign and a piñata in the form of Donald Trump leaned against 356’s green door. Signs on white sheets read “Fuck Artwashing†and “Vera Campbell, Keep Your Claws Off Boyle Heights,†a reference to the building’s owner.

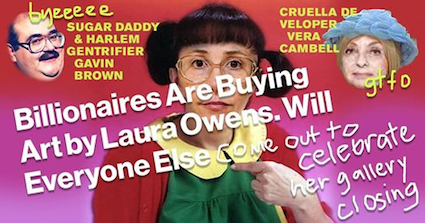

The closing party-cum-protest’s invitation, posted on Facebook by activist groups Defend Boyle Heights (DBH) and Boyle Heights Alliance Against Art Washing and Displacement (BHAAAD), showed 356’s cofounder, artist Laura Owens, as a bespectacled school girl—think Ugly Betty—and her dealer Gavin Brown, who, along with Wendy Yao and Owens, started the space in a former piano storage facility, as double-chinned. “For over two years,†it read, “the people of Boyle Heights and their artist allies constantly attacked the art galleries and now they are fucking leaving! Woo!â€

The gathering itself was less aggressive. Attendees lingered in the street. Around 4:30 p.m., one woman who lives at Pico Gardens, a public housing complex a few blocks away, took the first turn on a portable mic. She spoke in Spanish, and Elizabeth Blaney—a member of BHAAAD and the artist collective Ultra-Red, and a co-director of the Boyle Heights community organizing nonprofit Union de Vecinos—translated: “We were fighting an elephant and we are the ants, and with all of us little ants crawling up the elephant, we were able to tear it down.â€

For two years, protesters have been battling art spaces in downtown Los Angeles, arguing that they have been complicit in speculation in the low-income, Downtown-adjacent neighborhood of Boyle Heights; hence that piñata, which evoked Trump the notorious real estate developer.

But the story of downtown’s continuing development, and the protests arriving in its wake, is a complex one.

Installation view of “12 Paintings by Laura Owens and Ooga Booga #2,†2013, at 356 Mission, Los Angeles.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND 356 MISSION

In January 2013, when she opened 356 Mission, Owens told Artforum that said she wanted “to try something different, outside a system of institutional parameters.†Her painting sales helped fund the operation, and, early on, it was hard to tell if 356 was an artist-run space with blue-chip resources or a blue-chip space masquerading as artist-run. Programming varied from the academic to the eccentric. The poet and critic Wayne Koestenbaum performed an opera there; a group show of 300 works celebrated cats. For the first two years of its existence, hardly anyone writing about or exhibiting at 356 publicly discussed the space in relation to gentrification.

Owens and her cofounders opened 356 at the beginning of what would prove to be a gallery boom in Los Angeles, one that continues. Between 2013 and 2016, over 70 galleries opened in the city, many of them taking advantage of the fleeting affordability of large spaces in Downtown, East Hollywood, West Adams, and elsewhere. Established galleries, like Maccarone, Venus Over Los Angeles, and Hauser & Wirth had headquarters in New York or Europe. Some fledgling ones had goals similar to Owens’s, wanting to “break out of institutional parameters.†In early 2014, Robert Zin Stark opened a space called Museum as Retail Space (MaRS), to poke fun at the (often permeable) wall between art and commerce in both museums and galleries. The hierarchies he encountered in the gallery world frustrated him. “We want to be open to pretty much anyone who wants to be in love with what they’re seeing,†he told me around the time he opened. “The whole thing with Museum as Retail Space is ultimately a really earnest candidness.â€

Some galleries that moved in had to move out almost as quickly. In 2014, Harmony Murphy Gallery and Ibid. opened in two adjacent historic buildings on Santa Fe. Barely a year later, both received eviction notices. Their landlord, a company called Bolour Associates, wanted to raze the buildings, constructed in 1948 and 1910, respectively, and replace them with new lofts. The Arts District Neighborhood Council and L.A. Conservancy fought this and other demolitions like it, but Councilman Jose Huizar, who represents Boyle Heights and chairs the city’s Planning and Land Use Management Committee, introduced a Hybrid Industrial Live/Work Zone Ordinance that made ground-up development more attractive than preservation and required no special permitting to demolish buildings built before 1965. “Demand is high, project is certain,†Mark Bolour, Bolour Associates’ CEO, told me in an email in October 2015, shortly before Murphy and Ibid moved out.

The proliferation of galleries drew press attention, much of which focused on Downtown, and much of which positioned the galleries in a clichéd urban landscape, while leaving out that landscape’s residents. A September 2015 article in the New York Times described the new Boyle Heights area galleries giving Los Angeles an urban cultural density it “mostly lacks†and quoted Michele Maccarone, who had just opened her huge gallery next door to 356 Mission: “I like that we spent a fortune on security.†Five months later, another Times storydescribed the “rough-and-tumble streetscapes of the Arts District and nearby Boyle Heights.†It also quoted artist Sojourner Truth Parsons, a recent L.A. transplant. “You still have to make money, but [. . .] there isn’t that daily grind,†she said. “It’s mainly tacos and stray dogs and really nice people.†(Parsons, who was targeted on social media in the story’s wake, worked in nine different studios in three years, and left the city after losing her final space.)

Installation view of “Laura Soto: Flesh and Flood,†2018, at Museum as Retail, Los Angeles.

COURTESY MUSEUM AS RETAIL

The protests began in spring 2016, after local residents got wind of an artist-run space called PSSST that planned to open on 3rd Street, three blocks from the Pico Gardens Housing Project. At the time, I attended a meeting at Union de Vecinos, the community organizing nonprofit. A “fact sheet†circulated, written by a group called Pisssst and Resisting:

Fact: A silent investor bought the building and paid for the renovation.

Problem: [. . . ] Through this lack of transparency it appears their intention is not only to hide the name of the person investing but also protect them.

Fact: [Quoted from a PSSSST email] ‘We value process over product, transformational conversations, alternate economies of exchange, slowing down and showing up.’

Problem: Bullshit.

In July 2016, Matt Stromberg reported in Hyperallergic that Kean O’Brien, a former CalArts classmate of PSSSST’s cofounders, played a key role in organizing Pissst and Resisting. “I do not want to be a part of an art world where political work is made and put into white walled war zones,†O’Brien told Stromberg at the time. PSSST closed within a year, by which time Pissst and Resisting had dissolved into an older group called DBH and the recently-founded BHAAAD.

A few months later, a protest targeted all the galleries on Mission and Anderson Streets, which a located a few long blocks from residential areas—from 356, it takes about six minutes to walk east to the Pico Gardens and its surrounding recreation area, churches and schools. United Talent Agency Artist Space, run by the Hollywood agency, had its opening reception in the afternoon, before the protesters arrived. Venus Over Los Angeles’s director closed the gallery’s roll-down gate. Stark, owner MaRS, came out to engage. A chant overpowered him: “Step back and listen!â€

DBH and BHAAAD began targeting 356 Mission in earnest in February 2017. That month, protesters formed a picket line around 356 on the night Owens and several other artists were holding a meeting of their Artists Political Action Network (APAN), a reaction to Trump’s election. Art historian Nizan Shaked explained her decision not to cross the picket line in a piece for Hyperallergic: “[C]ommunication has fallen between the cracks of good intentions and it’s on us, the visitors, to stop and listen.â€

Charles Gaines, a cofounder of APAN, responded in a letter circulated online. “Dr. Shaked’s article,†he wrote, “was a failed attempt at journalism,†but “protesting the meeting at 356 makes one thing pretty clear to me, that gentrification is a complex sociological phenomenon that hardly anyone understands, even among social scientists.â€

In an open letter on Hyperallergic, B.H.A.A.A.D. wrote, “People whose rent increased 300% understand gentrification.†They linked to a bibliography that included sociological studies dating back to the 1980s.

Last September, writer and filmmaker Chris Kraus gave a talk at the City University of New York, to launch her biography of writer Kathy Acker. 356 Mission already had the book’s West Coast launch on its calendar. “I’m sure you’re aware,†said a young woman during the Q&A, “there’s a boycott called on by various activist groups in Boyle Heights.â€

“We’re not going to relocate, um, the event,†Kraus responded.

“Can I ask why, what compels you to actually think that it’s okay to displace people?†the questioner continued.

“You know,†Kraus said, “it would be really good if people from your group show up to that event and we can have this discussion at that event.â€

“It’s the same event,†a male voice called out. “Why can’t we have this conversation now?â€

The event in Los Angeles never happened.

In early November, protesters arrived at the opening of Owens’s midcareer survey at the Whitney Museum in New York, unfurled a banner and chanted “Give your keys to Boyle Heights!†Owens responded on 356’s website: “We hoped to find common ground to work toward the issues facing our community, but all of our ideas, such as working together on community land buy backs [. . .], were rejected.â€

Art writer and L.A. Tenants Union founding member Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal responded to Owens in a letter later included in the letterpress book, The Daily Gentrifier: “Is it listening when you only hear what you want to? I mean, you say you want to fight for housing justice, then seem to disagree with the people who are trying to get it.†Shaked asked, in a letter to the art quarterly X-TRA, whose board she later left after the publication held a screening at 356, “What kind of compromise could 356 Mission possibly offer that may resolve very real threats of eviction or deportation?â€

Installation view of “Charlemagne Palestine: CCORNUUOORPHANOSSCCOPIAEE AANORPHANSSHHORNOFFPLENTYY,†2018, at 356 Mission, Los Angeles.

BRICA WILCOX/COURTESY 356 MISSION

In late March, 356 Mission announced that it would close, sending out a letter calling its run “a labor of love,†done “with finite resources, and never intended to last forever.†The letter also noted that “[s]ome took issue with our impact on the neighborhood.†The space’s final show, a virtuosic, kitschy installation by Charlemagne Palestine, played with the notion of a “mission.†Palestine filled coffins with stuffed animals, and built immense piles of additional stuffed animals.

Last month, UTA Artist Space said that it would move in July to a new 4,000-square-foot space in Beverly Hills, not far from UTA’s headquarters, though Joshua Roth, who heads the art business, told me that activism wasn’t the reason for the new location. “An opportunity presented itself that offered greater connectivity to our Beverly Hills headquarters,†he said. “We had no issue with protesters.â€

But even as galleries are closing or relocating, development continues.

Venus Over Los Angeles closed abruptly in September 2017—“We are celebrating the closures,†wrote DBH on Facebook. The gallery did not respond to requests to comment on whether protests influenced their decision to vacate the space, but its owner, art collector Adam Lindemann, owner, art collector Adam Lindemann, had purchased a $9.75 million building on Imperial Street earlier that year, just across the river from Boyle Heights, filing plans for a 12-story live/work building. Tech companies are vying for former art spaces, the big-budget Sixth Street Viaduct Project is linking the thoroughly gentrified Arts District to still-resisting Boyle Heights with a new bridge, and Councilman Huizar is arguing that mass-scale demographic changes won’t occur in the area even as one of his former staffers lobbies for market-rate micro apartments in increasingly desirable Skid Row. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is mulling a satellite operation in fast-changing South L.A.

In April, Stark announced his decision to close MaRS during an appearance on the local public radio show Design and Architecture. The final show, of work by the under-known sculptor Lauren Szold, opens in June. Stark offered the “ceremonial and actual closing†of his gallery up to the protesters. He did not know exactly what this meant, he admitted when I met him at a coffee shop a week later. “I would want them to define that,†he said, saying he hoped the radio segment had not put them on the defensive. He continued, “I do think that white culture is symbolic of systemic violence and that’s where it gets its authority. DBH has given all this a narrative. No one in the art world knows what to do with this—it’s held [a] mirror up.â€

The gallery owners “try to minimize themselves by blaming other forces,†Blaney, of Union de Vecinos and Ultra-Red, wrote, when I emailed her a few weeks ago. She had already agreed to meet with Stark. “He speaks of ‘symbolic closing’ but what commitment is he making to the neighborhood [. . .]?â€

Stark met with activists at Union de Vecinos on May 4, walking in to find about a dozen people in ski masks. They discussed economic violence and neoliberal excesses, he told me via text. He left them to deliberate over whether he could help them. DBH did not reply to requests for comment on the meeting, but they posted on their website on May 17: “In only two short years our victories continue stacking in our favor. [. . .] We [are] still saying GTFO! [. . .] The fight to defend our ‘hoods is a fight for our collective survival.â€

Copyright 2018, Art Media ARTNEWS, llc. 110 Greene Street, 2nd Fl., New York, N.Y. 10012. All rights reserved.