An Artists’ Guide to Not Being Complicit with Gentrification

LOS ANGELES — We are Betty MarÃn, Heather M. O’Brien, and Christina Sanchez Juarez, and we met through organizing work in Los Angeles. Our conversations began in a group called School of Echoes, which operates as an open listening process of community-based research, popular education, and organizing to generate experiments in political action. Beginning in late 2012, the group has brought together organizers, educators, and cultural workers living and working in various communities throughout Los Angeles. School of Echoes is a space for critical reflection on the conditions in working class and poor communities, including (but not limited to) struggles against gentrification and for the human right to housing. In 2015, the group joined with other tenants in struggle to form the Los Angeles Tenants Union / Sindicato de Inquilinos de Los Ãngeles. LATU/SILA is a membership-based, tenant-centered movement fighting for the human right to housing for all. LATU/SILA demands truly affordable and safe housing and opposes the dismantling of rent-stabilized apartments. The union organizes against harassment by landlords, mass evictions, and displacement of people from their neighborhoods due to mass rent increases, as well as the repeal of the Ellis Act and Costa-Hawkins Act. LATU/SILA’s mission is to strengthen tenants’ political power through education, advocacy, and direct action.

We write in hopes that more artists will finally break with their sense of exceptionalism and consider their roles in gentrification. We recognize that art is an industry with a structural reality that must be acknowledged in order for artists to challenge their complicity in the displacement of long term residents in low-income and working class neighborhoods and fight against this. It’s important that people see the devastating impacts of securing housing in working class and poor neighborhoods, and setting up investment properties posing as art spaces. How can this loyalty to the notion of art as a pure form of positive change be reconsidered, particularly when such sentiment encourages the destructive endeavors of parasitic developers and landlords?

As far as how we see our own position in these debates and struggles, we constantly reckon with and interrogate our personal culpability and contradictions as people who participate in exhibitions and have jobs in the arts, be it in nonprofit educational institutions or otherwise. We hold ourselves accountable by organizing with our neighbors for the human right to housing.

We are in a moment where the connection between art, real estate, and the displacement of longtime residents is undeniable. How might artists take responsibility for how we alter people’s lives, in terms of the impacts of real estate speculation and gentrification? How do we refuse co-optation and engage locally with our neighbors? How are artists, curators, galleries, and museums complicit with the same finance capital that gentrifies neighborhoods across the globe? We ask all of this as we involve ourselves deeply with tenant rights groups, to listen and learn from political and social urgencies. We refuse to accept that pointing at problems is enough. Rather, we look to create a collective analysis, to “act our way into thinking †— a phrase borrowed from fellow organizer Leonardo Vilchis of Unión de Vecinos — which we’ve come to understand as the learning process that comes out of collective action, as opposed to relying on and residing only in theory. In this spirit, we share some of the lessons we’ve learned through our organizing and pedagogical work.

1.    Becoming involved in housing struggles — especially if we are part of a more “desirable†gentrifying class — is crucial. While deciding to commit to that work is not necessarily easy, a first step can be to understand the history and context you are moving into. If we move to a new block it’s essential to go beyond learning about who already lives there. We have to choose to stand with neighbors who have different needs. While we realize that as artists we contribute to the first wave of gentrification, we can choose to support our neighbors by joining them in demanding housing justice, by protesting unfair rent hikes, lacking repairs, or businesses that don’t serve the needs of long-term residents.

2.    As artists, we have to educate ourselves, especially considering that we might have racial, educational, or class privilege compared to our neighbors. We become part of the problem, another domino in the gentrification process, if we as renters don’t know our renters’ rights, or don’t take time to learn our rights and the reality of local conflicts. Abusive landlords operate on the notion that tenants do not know their rights. Learning our rights is the first step to building collective power.

3.    It is imperative to understand the need to find other ways of dealing with conflict or safety issues besides calling the police, given who the police serve and who the police jail and kill with impunity. We all have a stake in how our neighborhoods are made safe for everyone, and can choose to do this work without criminalizing the poor and people of color. Most galleries represent a white supremacist capitalist system that is protected by the police. For instance, in the community of Boyle Heights, each time those fighting to hold the galleries accountable for their impact on displacement and gentrification in their neighborhood stage a demonstration, the galleries have called the police, and have even accused the protesters of hate crimes. These accusations paint the galleries as victims while disguising the fact that they are protected by the state.

4.    As artists who participate in and support exhibitions, we must interrogate the spaces we choose to enter and work with. We must challenge what we do with our resources and privilege, on both a personal and a socio-political level. Consider for instance, if the spaces we support fail to ask questions about their structural impacts in a particular neighborhood — particularly if they are media-driven, contemporary art spaces. Regardless of their intentions (community engagement, bringing cultural programming to “underserved†populations, etc.) many art spaces ultimately serve as investment projects and property value boosterism for landlords, developers, and realtors. Is it worth supporting an art space when we know that it is currently contributing to or will contribute to someone losing their home?

5.    We must choose between prioritizing our own individualistic artistic careersor prioritizing the dismantling of oppressive structures. There are no places without contradiction, nor places where we can be absolved of reinforcing oppressive structures. Instead, we must reorient our priorities so that we can be honest about what we are actually working towards. It takes time to learn how to point at a problem, yet too often we feel the work ends there. When it comes to art, there’s a certain cultural capital gained by criticizing capitalism, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that we are putting anything on the line to dismantle it. In far too many instances, the violence of the status quo is actually protected, guarded, and upheld in smug, self-assured condescension by artists with careers to protect when those who seek to rattle the cage more vigorously violate liberal taboos like “tone†and “unity.â€Â If we get involved in anti-oppression struggles, listen, and are aware of privilege and the differing crises that surround us, it’s difficult to see an individual art career as something worthwhile. We’ve seen many artists with visibility (i.e. artists with gallery representation or those who have received major recognition of their work through awards or grants) who dismiss and criticize the artists and local organizers who choose to stand with the local neighbors of Boyle Heights in the form of social media rants and public media outlets (calling them misguided and naive). How might we tune our listening away from those with powerful art world platforms to those most impacted by gentrification?

6.    We must ask about the power of art spaces to decide who is included in the first place. This is a moment of extreme tokenism, one in which exhibition spaces co-opt political movements or artistic identities and pat themselves on the back for their diversification, for their “radical†inclusion. We see this in museums, where curators invite grassroots organizers to do educational outreach work. Doling out temporary visibility does not decentralize the white ruling class that presides over the art world, in the form of, let’s say, Wall Street bankers sitting on the board of a contemporary art museum. What is an art institution’s intent when they only temporarily feature a social movement in their space?

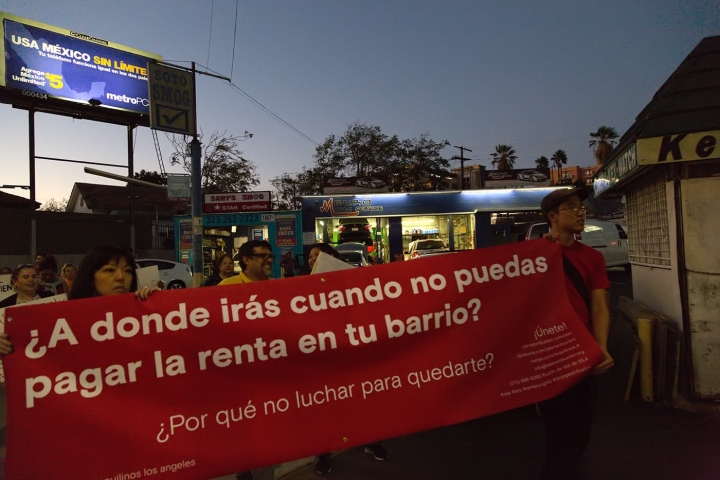

Vermont & Beverly Local, LA Tenants Union Anti Landlord Harassment Action, 2016 (photo by Timo Saarelma)

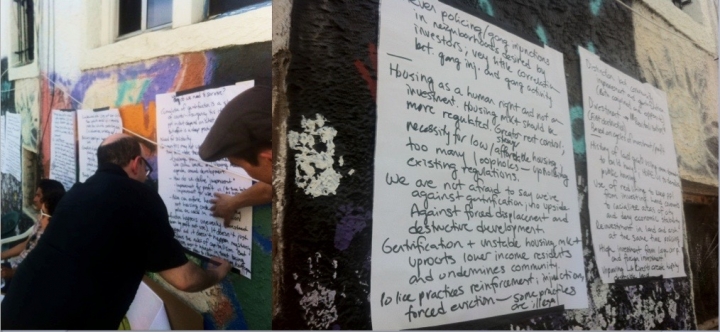

The struggles against the galleries in Boyle Heights have taught us valuable lessons and we have learned about housing struggles through local organizing with fellow tenants. To us, this work is about building spaces of “intimate solidarity,†a term borrowed from fellow artist in struggle Patricia Vazquez. We’ve come to understand this term as political action that is centered in relationships, love, and care. We realize that the mainstream media has chosen to erase the voices of long-term residents who explicitly and articulately describe the historical and structural analysis behind their resistance. We stand with the long-term residents of Pico Gardens and Aliso Village in Boyle Heights who have made it clear they do not want art galleries in their neighborhood. However this stance is not a refusal of all art. We see art as part of how people struggle and resist in life. Art becomes alienating when entities and individuals refuse to acknowledge their personal and structural impacts that contribute to gentrification. The critical voice of the artist is lost when it’s instrumentalized in processes of displacement.

The debates around these issues have certainly become intense, but they’re nothing compared to the trauma of being evicted from your home of over thirty years. How might we encourage popular education and empowerment without permitting artists and galleries to ride the wave of gentrification, as if absolved from questions of property speculation and skyrocketing rents? What if we see our role as artists as being deeply tied to the health of our neighborhoods?